What do one of the Old West’s most successful bank robbers, a champion race car designer, and Studio Science all have in common?

Growing up as I did in New Mexico, I was destined to literally walk in the footsteps of our country’s most notorious Wild West outlaws, albeit, in a different sort of way. Take legendary cattle rustler and frontier soldier Billy the Kid, for example. He operated in the same Lincoln County hills that sheltered me from truancy officers when a full day of school was impossible to imagine. And Sheriff Pat Garrett handed The Kid his fate near the same lake where I dispatched several offending rainbow trout.

Billy the Kid was good, if a bit reckless, and that lack of foresight contributed to his demise at just 22 years old. Not that it was unusual for the outlaws of Billy’s day to take a “ready-fire-aim” approach to their craft.

But there was one. A bank and train robber who saw things differently. A contemporary of The Kid who, despite his high profile, managed to make it to the ripe old outlaw age of 42–and maybe longer if you believe the stories.

His secret? Systems thinking.

Butch Cassidy was born in Beaver, Utah in 1866. Raised in a home that could barely make ends meet, he became the family’s sole breadwinner after his father passed. Butch began his working life as a ranch hand at age 13, and at 18 left home to become an independent miner in Telluride, Colorado. Unfortunately, most of the major claims had already been spoken for, and Butch instead found himself breaking rock and hauling gold for the benefit of others. At 23, he finally took a look at his paycheck, then eyed the nearby San Miguel Valley Bank, and decided whose money he liked better.

Prevailing heist techniques of the 1880s suggested that the robbery Butch was about to attempt wouldn’t end well. Smash-and-grab operations at best, bank jobs were typically informed by only impulse and whiskey. When they were over, thieves usually found an angry town mob or trigger-happy sheriff’s deputy waiting to gun them down.

But Butch wasn’t typical. He worked weeks in advance, learning everything he could about the bank, and imagining what might happen in the immediate aftermath of the hold-up. As one Old West historian notes:

Parker knew that it was not just about where the money is, but knowing when it will be at its peak. When will the cash arrive? Who handles the Cash? How many people are in the building at the time when the cash is at its peak? And more importantly than that, how will I make my escape?

Butch planned an escape route and set up horse relays along the way, so he and his crew could outpace any pursuing sheriff’s posse. He built alliances with homesteaders along the route, to guarantee safe passage or secure potential hideouts. As our historian says, “He planned the escape even better than the hold-up”

In other words, Butch adopted a systems approach for the job–an assessment of all the people, places, things, and events that would inform it, and everything that could influence its outcome. And because of this approach, the San Miguel Valley Bank job of 1889 became a $25,000 payday–almost one million in 2022 dollars.

In total, Cassidy and his band of outlaws (including, eventually, the Sundance Kid) robbed no more than four banks, four trains, and a payroll company. But they all employed systems thinking, and became a feat greater than most of his contemporaries could claim. Systems thinking possibly contributed to another Cassidy “innovation:” nobody was ever killed, or even severely injured, in any of his robberies.

Far removed from my outlaw years in New Mexico, I find myself living in Indianapolis, Indiana and working as a brand strategist. The racing heritage of my new home, along with my work in a design agency, helps me to recall another systems thinker I’ve discovered.

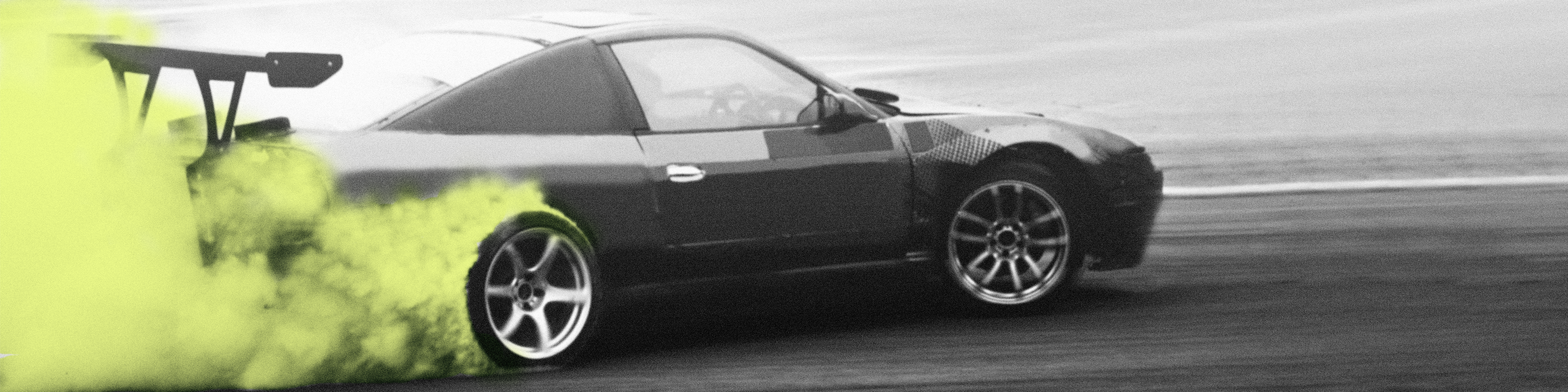

In his book Design Thinking, researcher and educator Nigel Cross profiles car designer Gordon Murray, whose innovations while working with the Brabham and McLaren F1 racing teams in the 1980s led to several championship seasons. Just as Cassidy knew that a bank robbery involved more than a safe, Murray understood that a race involved more than a car.

Yes–the fastest car usually wins the race, and weight is the enemy of speed. And so is a complete mid-race stop. Because of this, pit stops (pauses by a driver during a race for fuel, new tires, mechanical adjustments, etc.) weren’t a deliberate part of F1 racing strategy prior to the early 1980s. And while this seems to make perfect sense, Murray, during his time with the Brabham F1 team, rethought pit stops and their place in the entire system of a race.

He began by making his team’s car lighter (and faster) by reducing the size of its fuel tank. This of course necessitated more refueling stops. But these stops were planned, rehearsed to perfection, and scrutinized down to the second. He also developed a pressurized fuel system to deliver fuel to the car faster. Murray even filmed pit stops to spot opportunities for more efficiency.

Another crucial pit activity is the changing of worn or damaged tires. For optimal performance, fresh sets of tires require warming; this was previously accomplished by speeding them around the track for a few laps, with the acceptance that some time would be lost in the process. But Murray chose not to accept it, and instead developed a method of pre-warming of tires in the pit area via the use of a gas-fired stove. And by considering even the tools used to change tires, Murray was able to improve the pneumatic gun that removes and applies the F1 wheel nuts.

While overall average pit times increased, the advantages gained from Murray’s new pit system made for overall faster lap times. As Cross puts it: “…radical innovation was driven by…how a total systems approach was adopted.” It was innovation that contributed to two Driver Championships for the Brabham team, and four combined Driver and Constructor Championships for McLaren.

In my work at Studio Science, I feel connected to these innovators. To Butch Cassidy, a robbery was about more than a safe. To Gordon Murray, a race was about more than a car. At Studio Science, a brand is about more than a logo or a tagline. As a colleague of mine pointed out in an earlier post, a brand is “the total experience that you provide anyone who comes in contact with your company.”

To create that total brand experience, we consider the entire system–the people, things, and events–that inform and are informed by it. It includes the employees who fly your banner every day. The customers who turn to you to fulfill a need. The market that grows and changes around you, and it’s the competitors you’re up against. At Studio Science, we explore the whole system, and in doing so, create brands and experiences that people want.

NOTES

Maggio, J. (Director). (2014). Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid [Film]. American Experience Films.

Cross, N. (2011). Design Thinking: Understanding How Designers Think and Work. Berg